Introduction

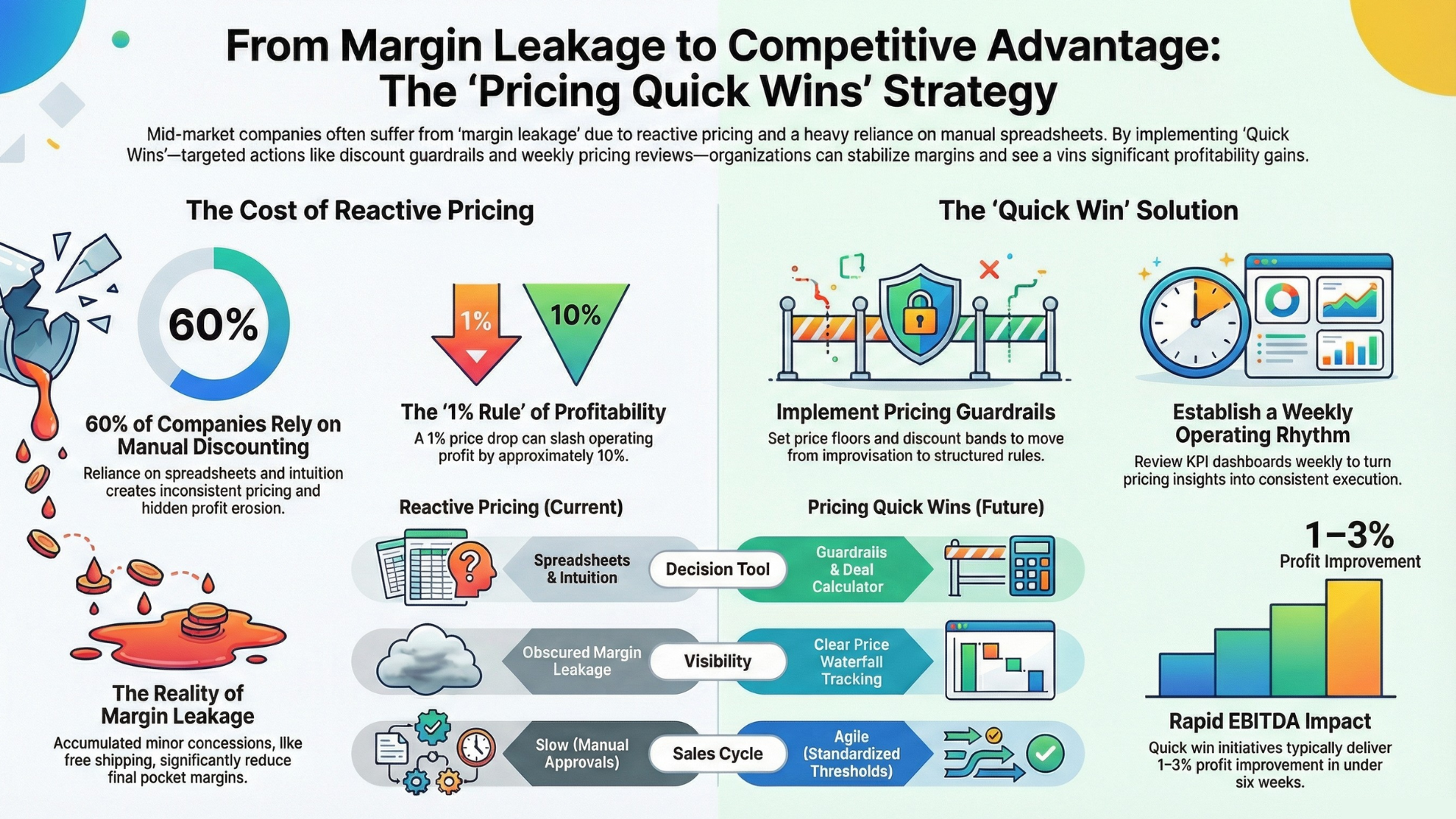

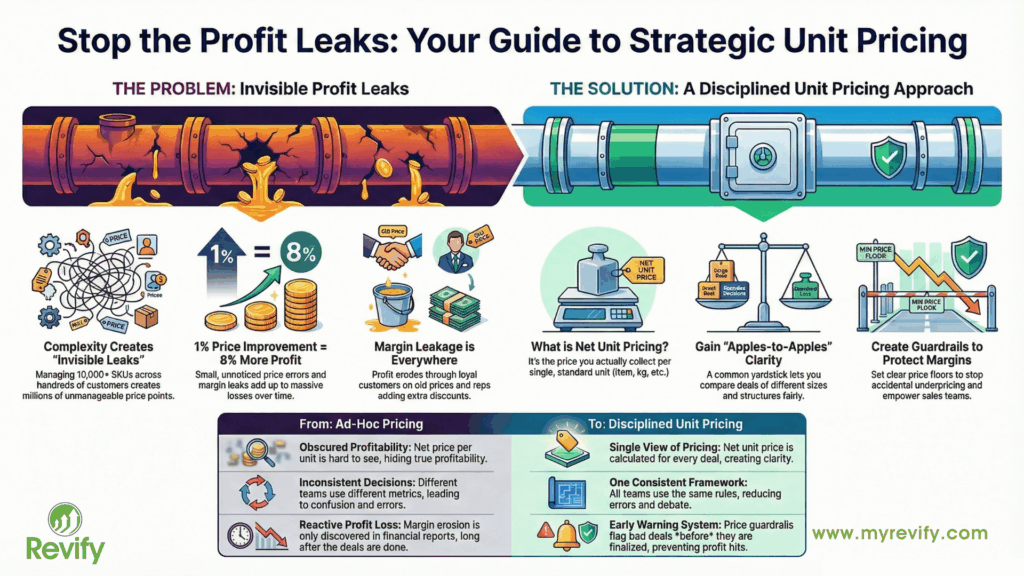

For small and mid-sized manufacturers and distributors, pricing is now a daily, high-stakes challenge. With 10,000+ SKUs and hundreds of customers, millions of price points emerge from different quantities and terms. Intuition alone cannot handle this complexity, leading to “invisible leaks” in profitability—loyal customers on outdated prices, reps adding extra discounts, or costs eroding margins. This silent margin erosion is a constant threat for SMBs.

Recent economic pressures have amplified the issue. Inflation and supply shocks raised input costs, forcing price adjustments or margin losses. Large brands tried shrinkflation, but customers noticed. In B2B, you need transparency and control—stealth tactics don’t work. Yet costly, slow enterprise pricing software is out of reach for most SMBs, while manual pricing is error-prone. Only about 2% of mid-sized firms achieve high pricing analytics maturity, as complex tools and ad-hoc processes leave most struggling.

The next wave of pricing strategy for SMB manufacturers and distributors is not about gimmicks or one-off fixes – it’s about managing your price-per-unit across all products, customers, and deals without giving margin away. In other words, it’s about treating unit pricing as a strategic discipline, not a mere afterthought on an invoice. This article examines how unit pricing can assist smaller companies in addressing pricing complexity, optimizing margins, and enhancing profitability. We’ll define what unit pricing really means in a B2B context, walk through examples (from managing thousands of SKUs to dealing with rapid cost changes), and outline practical steps to implement unit pricing in your business. Along the way, we’ll highlight challenges unique to SMBs – such as high SKU counts, lightning-fast transactions, limited pricing staff, and the inability to afford long, enterprise-scale projects – and demonstrate how a disciplined unit pricing approach can address them.

Bottom line: By making unit pricing a cross-functional language and control system in your company, you can turn chaotic pricing into a competitive advantage. You’ll be able to compare offers that were never designed to be compared, spot margin leaks in time, and empower your team to make data-driven pricing decisions. The payoff is real – even a 1% improvement in realized price can increase operating profits by roughly 8% – and for resource-strapped SMBs, that can be transformative. Let’s dive in.

What is Unit Pricing? (Definition and Key Concepts)

Unit pricing is the price of a product or service expressed per a single, standard unit of measure. In simple terms, it tells you how much one unit costs – whether that unit is one item, one kilogram, one liter, one pound, or any other measure that makes sense for your business. You calculate it by dividing the net price (the actual amount you collect after any discounts or rebates) by the quantity in the transaction’s unit of measure. For example, if you sold a case of 24 units for a net price of $120, the unit price is $120 ÷ 24 = $5 per unit.

Understanding this definition is straightforward, but applying it in a business with many products and deal types can be tricky. Let’s break down a few key concepts and distinctions:

Unit Price vs. Total Price

The total price is what the customer pays for the whole package or line item – for instance, $120 for a case of parts, or $500 for a bulk order. The unit price converts it to a comparable basis, such as $5 per part or $0.50 per unit. This conversion is powerful because it lets you compare offers of different sizes or formats on an apples-to-apples basis. It’s so fundamental that consumer protection regulators require unit prices on retail shelf tags in many markets (to help shoppers compare value) . For your business, the unit price is not just about complying with a law – it’s about gaining insight. It allows you as a pricing leader to line up deals that “weren’t designed to be easy to compare” and evaluate them with a common yardstick.

Unit Price vs. Unit Cost

Don’t confuse unit price with unit cost. Unit cost refers to the cost you incur per unit, including production costs and other cost-to-serve elements such as freight or handling. The unit price is the amount you charge per unit. The difference between the two is your unit margin. You need visibility into both. A common mistake is to build a nice unit price view for all your SKUs, but forget that not all units cost the same to produce or deliver. For example, one SKU might have a higher freight cost or special handling requirements that aren’t immediately apparent from the price. If you only look at unit prices and ignore costs, you might think you’re doing fine on an item while quietly losing money on it. Practical rule: Don’t look at unit price in isolation – always pair it with at least a rough view of unit margin. This ensures a “great price” isn’t actually a bad deal once you factor in costs.

Unit Price vs. List Price (Why Net Unit Price Matters)

This distinction is crucial for B2B firms. List price (or “book price”) is the published starting price. The net price is what you actually pay after accounting for all discounts, rebates, promotions, and allowances. For unit pricing to be a useful management tool, it must be based on the net price, not the list price. Why? Because any unit price calculated on list price is a fiction – it’s a number your P&L never actually sees in full. Accounting standards treat discounts and rebates as part of the transaction consideration, meaning they effectively reduce the price you realize. If your reports show a unit price of $5 based on the list, but after a 10% discount, the actual unit price is $4.50, managing the business based on the $5 figure is managing on an illusion. Always use the net unit price as your metric, so you’re aligning with reality. (In a moment, we’ll see how failing to do this can lead to big misjudgments in pricing.)

In summary, unit pricing takes whatever you’re selling – be it a case of 100 screws, a pallet of product, or a one-off service project – and boils it down to “price per unit” on a consistent basis. This could be dollars per item, per pound, per gallon, per thousand pieces – whatever base unit makes sense. It provides a common language for comparing deals of different sizes and structures. Most importantly for SMBs, it turns pricing into a measurable, governable process. Instead of debating if a $10,000 deal is good or bad in total, you can break it down to “we sold those units for $2.13 each” and compare that to your targets, costs, and other deals.

Why SMBs Struggle with Pricing (and How Unit Pricing Helps)

Before exploring unit pricing as a solution, let’s clarify the pricing challenges that small and mid-market manufacturers/distributors face. These challenges set the stage for why unit pricing, used strategically, can be such a game-changer.

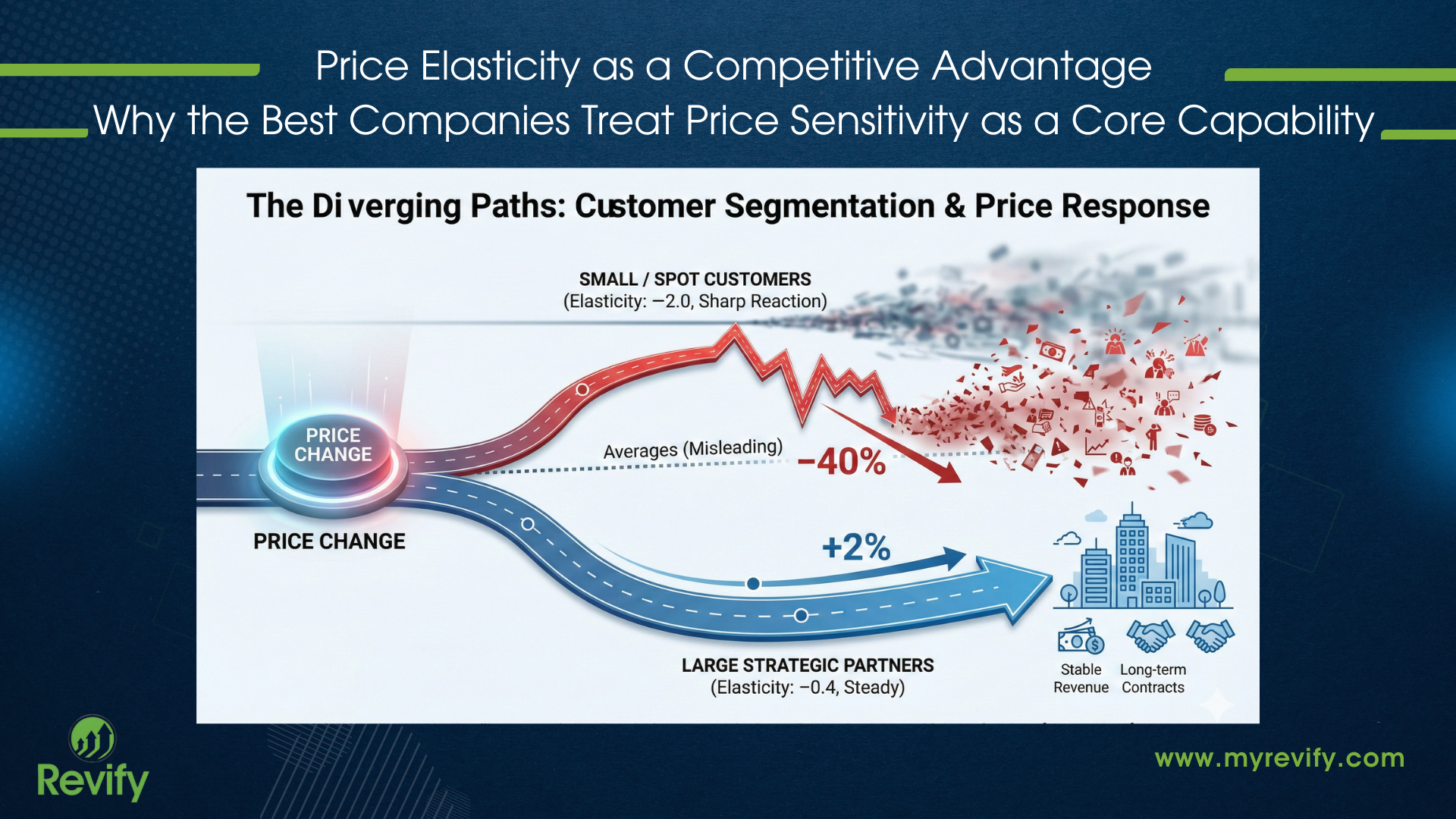

- Thousands of SKUs and Transactions: SMB distributors often carry extremely broad product catalogs (10k+ SKUs), and manufacturers may have extensive product lines or component variations. When you multiply SKUs by customers, by different order sizes, you get an explosion of price points – easily tens of millions of possible price combinations in a business. Managing this with manual reviews or gut feel is impossible. The complexity means most pricing decisions default to rules of thumb or inertia, and that’s when margin leaks start appearing everywhere.

- High Transaction Velocity: Unlike enterprise giants that often negotiate annual contracts, many SMBs process orders daily or weekly, with price decisions made at the line-item level. A regional distributor, for instance, might process hundreds of orders a day. This high velocity makes it hard to “catch” mistakes. If a pricing error or an out-of-date price is in your system, it could be applied dozens of times before anyone notices – unless you have a mechanism to systematically catch outliers (which unit pricing can provide).

- Limited Pricing Infrastructure: Large companies often have dedicated pricing departments, sophisticated pricing software, and data scientists on staff. Mid-market firms usually don’t. You might have one pricing manager (or none at all), and rely on salespeople or ERP defaults to set prices. Tools are often basic – lots of Excel, perhaps an ERP price list module, and rarely anything more advanced. This makes it hard to see what’s happening. It’s common for different teams to have different data or assumptions (sales has one spreadsheet of “their” prices, finance has another view of profitability). The lack of a single source of truth leads to inconsistent pricing and internal debates, rather than informed action. And while leaders know they’re “data rich but insights poor,” traditional enterprise pricing solutions are too costly and heavy to fill the gap. (Why? These big tools often require 6-18 month implementations and dedicated IT resources – a marathon project few SMBs can afford .)

- Margin Leakage Everywhere: Without strong controls, margin leaks in multiple ways. We touched on a few earlier – legacy customers were still paying outdated low prices, sales reps were giving extra discounts to close deals, and cost increases were not passed through promptly. To give concrete examples:

- A “loyal” customer might still be paying a price set seven years ago when they bought higher volume; today, their volume is smaller, and costs are higher, but they haven’t been repriced, eroding your margin on that account.

- A rep might throw in an extra 5% discount as a goodwill gesture, not realizing that if the item’s base margin was only 20%, the extra 5% discount actually wipes out 25% of your profit on the deal. (Small percentage points matter a lot in low-margin products.)

- Supplier cost increases – say raw materials or parts costs rose 5% this quarter – may not fully make it into your pricing, especially if you update prices infrequently or only when sales scream. The result is a quiet margin compression: what used to be a 25% margin product might drift down to 15% margin before anyone acts.

- These leaks are often small on each transaction but massive in aggregate. Your profit isn’t usually lost on one big mistake – it’s the accumulation of many small underpriced moments. And because they’re dispersed across SKUs and customers, they often go unnoticed in the noise of daily business.

- Broad Portfolios and Fast-Changing Costs (Distributor Challenges): Distributors, in particular, operate on razor-thin margins and face constantly changing supplier prices. In an inflationary period, you might receive price increase notices from dozens of suppliers every month. If you’re only looking at your list prices and assuming all is well, think again. Often, the list price stays the same while the net realized price erodes, due to more discounting or delayed updates. For example, if your supplier raises the cost of a product by 10% over the year and you don’t adjust your customer pricing in a timely manner, the product’s unit margin has shrunk significantly (the “cost-creep” scenario). Tracking only list prices is insufficient – you need visibility into net unit price and unit margin, so you catch these erosions early. A broad portfolio makes this hard; you can’t manually check hundreds of items each month. This is exactly where a unit pricing discipline pays off, by programmatically highlighting which items’ net margins are off norm.

- Innovation and Lifecycle Pricing (Manufacturer Challenges): Manufacturers face specific challenges related to new products and end-of-life products. When launching a new product, pricing is often a best guess – product managers might set a low introductory price to penetrate the market or bundle it with other products. If not monitored in unit terms, a new product can accidentally undercut the rest of your portfolio. (For instance, a new pack or model might have a lower $/unit than your core product once you standardize the units, unintentionally creating a better deal than the core product.) Conversely, when retiring or clearing out a product, companies often apply steep discounts to move the inventory. Both situations – introduction and clearance – are prime time for margin leakage. You might accept a lower margin on a new product for strategic reasons, but you’d better know how much margin you’re giving up and for how long. Similarly, if end-of-life discounts drop unit prices below your normal floors, you want that visibility. Many SMB manufacturers lack a formal process to track these scenarios; as a result, new offerings sometimes cannibalize margins from existing lines, and end-of-life sell-offs can turn healthy margins into losses. Unit pricing analysis can flag these issues. For example, it can show that your “Version 2” product is selling at $0.95/unit (in equivalent terms) while the older Version 1 still sells at $1.10/unit – a sign that Version 2’s pricing might be too low relative to value. Or it can reveal that the clearance sale on last year’s model has pushed its unit price below cost, so you can set an appropriate floor or bundle strategy.

Given these challenges, it’s clear that doing nothing or relying on gut feel is costly. Many mid-market firms know they have a pricing problem (“we’re leaving money on the table”), but feel stuck because the solutions seem out of reach. This is where unit pricing as a discipline comes in. It offers a pragmatic, data-driven approach to managing pricing that suits the scale of an SMB. Instead of boiling the ocean with a huge system, you focus on a core set of metrics and rules that expose where you’re giving away margin. In the next sections, we’ll demonstrate how treating unit price as a common language can unify your team – from sales to finance – and pinpoint the areas that require action.

Unit Pricing as a Strategic Lever (Not Just a Metric)

Most companies are familiar with the concept of unit price in some form – but usually in a narrow context (such as the price per pound on a label or a quick calculation an analyst performs when needed). Treating unit pricing as a strategic lever means elevating it to a central role in your pricing decisions and governance. It becomes a cross-functional language that everyone understands, serving as a yardstick for nearly every deal. Here’s what that does for you:

- Clarity Across the Board: When every product’s price can be viewed on a per-unit basis, you cut through a lot of complexity. A bundle of 5 items for $1000 and a single-item sale for $50 can be directly compared in unit terms (e.g., dollars per item, or per some standard quantity). This exposes mispriced items quickly. In many companies, different teams use different units or assumptions (one team talks in terms of price per case, another in terms of price per pound, etc.). By standardizing on one unit per category, you avoid debates about conversion and focus on the real question: is this price too low or high? Unit pricing enables apples-to-apples comparisons, which is the foundation of disciplined pricing.

- Better Price Architecture & Product Mix Decisions: Price architecture refers to the relationship of prices across your product line or pack sizes – the “ladder” from smaller units to bulk, or from economy versions to premium versions. Unit pricing is the lens that keeps your price architecture rational. For example, you may sell a product in both 10-pack and 50-pack formats. You intend the 50-pack to have a lower unit price (a volume discount). On list price, maybe it does. But once real discounts are applied, does that still hold? It’s not uncommon to find that after various deals, the larger pack is actually cheaper per unit in a way that slashes your margin. Or maybe a new product was introduced at a slight discount and ended up undercutting the unit price of the main product. Unit price analysis will flag these ladder breaks. You can quickly see if your “good/better/best” offerings are aligned, or if, for example, the “value” pack is ironically offering the worst value per unit. Armed with that insight, you can adjust list prices, discount policies, or packaging strategies to address the anomalies. In short, unit pricing helps design and maintain a coherent pricing structure – one that makes sense to customers and preserves your intended margins.

- Promotion and Discount Discipline: Promotions, discounts, rebates – these are often necessary to win business, but they are also where margin goes to die if unmanaged. SMBs might not think of “promotions” the way a big consumer goods firm does, but you likely have analogues: seasonal sales, volume discounts, free freight deals, etc. The key is to evaluate any such offer in terms of equivalent unit price. For example, if you give “10% off” on a $1,000 order, or run a “buy 5 get 1 free” deal, what does that translate to as a unit price? Often, teams focus on the percentage discount (“10% isn’t too bad”), but when converted to a unit rate, that promotion may be effectively cutting the price per unit by 20–30%. Unit pricing forces you to confront that. It turns abstract discounts into concrete per-unit economics. This discipline helps in a few ways:

- You can set unit price floors or guardrails for promotions to ensure optimal pricing. For instance, “any promo we run must still yield at least $X per unit, which is our break-even unit price.” This prevents well-meaning sales initiatives from gutting your profitability.

- You can compare different discount structures fairly. A 15% off deal vs. a “buy 10 get 2 free” might appear different, but the unit price will tell you which is more aggressive. This guide helps you choose promotions that achieve the desired volume lift at the lowest possible margin cost.

- Over time, you can analyze which promotions actually drove additional volume worth the margin they cost. Many companies find, as McKinsey famously reported, that a large share of promotions or discounts loses money – one study showed that about 59% of promotions were unprofitable, with that number even worse (72%) in the U.S. sample. By tracking unit prices and the volume outcomes, you can pinpoint which tactics are “paying for themselves” and which are pure leakage.

- Guardrails and Deal Governance: In B2B settings, especially, having clear pricing guardrails is critical. Unit pricing provides a very tangible way to enforce them. Instead of abstract margin percentages buried in spreadsheets, you can say, for example, “We will not sell below $10.00 per unit on this category, except by explicit exception.” That is easy for a salesperson to understand and for management to monitor. If a special deal is cut at $9.50 per unit, it should trigger an exception process. Many mid-market firms lack this kind of governance – every salesperson negotiates differently, and by the time finance sees the results, the margin has already been given away. With unit price guardrails, you create accountability in the moment. Salespeople have a reference point (and ideally, tools that display the unit price as they quote), and management can review a simple exception report of any sales that fall below the floor. This doesn’t eliminate flexibility; rather, it ensures that any sub-floor pricing is a conscious choice made for a good reason (e.g., a strategic account, or an end-of-life clearance) and not an accidental outcome. The benefit is twofold: you protect your floor margins on the vast majority of deals, and when exceptions do happen, they are documented and can be learned from. Over time, this fosters a culture of price discipline, even in smaller companies.

- Cross-Functional Alignment: One subtle but powerful effect of implementing unit pricing rigor is that it brings teams together. As mentioned, unit price becomes a common language for sales, finance, marketing, and operations. Finance might love the idea of improved margins, but sales need to see how it helps them too. With clearer unit economics, sales can identify which deals are truly “good deals” (profitable) versus just big revenue numbers that don’t translate to profit. It also arms them with better justification for price increases – instead of “we need to raise price by 5% because management said so,” they can say “our cost per unit went up, and our target unit price is $X to stay healthy.” In smaller organizations, people wear multiple hats; having a single source of truth (unit price metrics) reduces internal friction. Instead of arguing whose spreadsheet is right, teams can focus on real trade-offs – like, “If we give this discount, the unit price will drop to $Y, which is below our threshold – do we have a plan to make up that margin elsewhere?” That is a higher-quality conversation than “Did you include the rebate in your calculation?”

In sum, unit pricing used strategically tightens up three critical areas: price architecture, promotion/discount effectiveness, and governance. It transforms pricing from a black box (or the wild west) into a more scientific and transparent process. Importantly for SMBs, it does this in a scalable manner. You don’t need 10 analysts to manage pricing; a few key metrics and business rules can automate a significant amount of the heavy lifting. Think of unit price as the control knob for your pricing engine – once you set the right parameters (units, floors, etc.), you can tune your pricing outcomes much more finely than before.

Next, let’s examine some illustrative examples of how unit pricing reveals issues and informs decisions in manufacturing and distribution environments.

Scenarios and Examples: Unit Pricing in Action

Sometimes the best way to see the value of unit pricing is through examples. Below are two practical scenarios (simplified for illustration) showing common margin leakage problems that unit pricing can uncover for SMBs – one for a manufacturer and one for a distributor. (These are based on real patterns companies encounter, with numbers adjusted for simplicity.)

Scenario 1: Volume Discounts Undercutting Margin (Manufacturer)

Context: A mid-sized manufacturer sells the same product in two pack sizes. Let’s say a 12-pack and a 24-pack. The larger pack has a lower list price per unit by design (to encourage bulk buying).

- Pricing Setup: The 12-pack lists for $18 (which is $1.50 per unit), and the 24-pack lists for $32 (about $1.33 per unit). At first glance, this pack-price ladder appears logical – the larger pack offers a roughly 11% lower unit price on the list ($1.33 vs $1.50).

- Reality of Discounts: In practice, however, the manufacturer offers larger average discounts on the larger pack, as big orders often attract more negotiation. Suppose the average off-invoice discounts and allowances total 10% on the 12-pack sales, but 22% on the 24-pack sales (bigger customers bargaining harder). Now compare the net unit prices:

- 12-pack net unit price = $(18 \times 0.90) ÷ 12 = $16.20 ÷ 12 = $1.35 per unit.

- 24-pack net unit price = $(32 \times 0.78) ÷ 24 = $24.96 ÷ 24 = $1.04 per unit.

- Margin Impact: Assume the product’s cost is about $0.90 per unit to produce. For the 12-pack, the gross profit is roughly $1.35 – $0.90 = $0.45 per unit. For the 24-pack, it’s $1.04 – $0.90 = $0.14 per unit. In percentage terms, the larger pack’s gross margin is only ~13%, versus ~33% on the smaller pack – a huge drop.

- What Went Wrong: The list prices suggested a reasonable strategy, but list-based architecture “failed” in the real world. The higher discounts on the larger pack inverted the economics. The company is sacrificing a lot of margin to sell in bulk – far more than intended, and perhaps more than necessary.

- Unit Pricing Insight: A unit price analysis would have highlighted this immediately. Instead of just seeing revenue by product, management would see that the net unit price for the 24-pack is far below that of the 12-pack (and below any acceptable margin threshold). They could then ask why – the discount is too high? Is the cost higher than we thought for serving bigger orders? Should the list price gap be smaller to begin with? This scenario also underscores why using net price is critical: if you only looked at the list price ladder, you’d think everything was fine, while in reality, your profit per unit was collapsing on the larger pack.

- Outcome: With this visibility, the manufacturer can take action, such as tightening discount approval for large packs, adjusting list prices, or ensuring that if a large pack receives a significant discount, it’s tied to a lower cost-to-serve (e.g., the customer picks up the freight). Even a modest correction can have a big impact. Remember the earlier point: a 1% improvement in realized price can lift operating profit by ~8%. In this case, increasing the price from $1.04/unit to $1.10 or $1.20 could substantially boost profitability on a high-volume item.

Scenario 2: Accounting for Freight and Rebates (Distributor)

Context: An industrial distributor sells many products, but let’s take a single item (e.g., a type of fastener) sold in different package sizes. They offer cases of 100 units and 250 units. The larger case has a better per-unit price, and one version includes delivery.

- Pricing Setup: A 100-unit case is priced at $120 (customer pickup), and a 250-unit case is priced at $280 (this price includes delivery to the customer). At face value,

- 100-case unit price = $120 ÷ 100 = $1.20 each.

- 250-case unit price = $280 ÷ 250 = $1.12 each.

- Regarding the ticket price, the 250-pack appears to be cheaper per piece, as intended.

- Incorporating Cost-to-Serve: Now, let’s factor in the additional costs or discounts:

- Freight: The 250-unit case price included delivery. Suppose delivering that case costs the distributor $15. Effectively, the net revenue from that sale is $280 – $15 = $265 (if we allocate the freight cost). Now the adjusted per-unit revenue is $265 ÷ 250 = $1.06 each for the 250-pack.

- Rebates: Assume this customer also qualifies for an end-of-year rebate of 2% on total purchases (a common incentive in distribution). That would further reduce the net realized price. Applying 2% to $1.06 brings it to roughly $1.04 per unit.

- Meanwhile, the 100-pack had no delivery (pickup) and perhaps no rebate for that customer tier, so it stays at $1.20 net per unit.

- Comparison: After these adjustments, the 250-pack still has a lower unit price ($1.04 vs. $1.20), which is acceptable – we expect bulk purchases to be cheaper. However, notice how much lower it actually went once we accounted for real-world factors: from a $1.12 list price down to $1.04 net per unit. That extra ~$0.08 might be the difference between a decent margin and a razor-thin one.

- The Bigger Issue – Visibility and Consistency: In many distributors, scenarios exactly like this play out, but sales and finance might not agree on the math. Sales might quote $280 delivered and think in terms of $1.12 each (list). Finance will subtract freight and rebates after the fact, resulting in a net amount of $1.04. If there isn’t a shared unit price calculation, you get endless arguments: “That deal was fine, we sold at $1.12 each, which is above our $1.10 target” vs. “No, we only realized $1.04 each, below our floor, we lost margin.” Most mid-market B2B teams lack a repeatable method for translating all these factors (freight, rebates, discounts) into a true net unit price. The result is confusion and sometimes conflict between departments.

- Unit Pricing Insight: By implementing a consistent unit pricing approach, the distributor can standardize this calculation. Every deal is evaluated in terms of net unit price at the time of quoting/approval. In our case, the sales representative would know that delivering the 250-case shipment effectively “costs” $0.06 per unit, and the rebate another $0.02, so the net offer is really $ 1.08 per unit. Management can set a policy that states, for example, “we don’t go below $1.05 on this item without higher approval.” That way, both sales and finance are on the same page – the deal economics are clear, and if an exception is made, everyone knows it and why.

- Outcome: This brings discipline to pricing agreements and contracts. Over the course of a year, it prevents the scenario where the exception becomes the rule. Perhaps one deal at $1.04 is acceptable for a large customer, but if half your sales end up at that level due to various concessions, you’ve significantly reduced your margin. Unit price monitoring ensures that kind of creeping margin erosion is caught and addressed. It also builds trust internally: finance trusts the sales deals because they know the proper adjustments are considered upfront, and sales trusts finance’s metrics because they’re speaking the same language (net unit price).

(The above scenarios are simplified, but they reflect very real issues. A snack manufacturer’s case study showed how the net margin per unit of a larger pack fell to almost one-third of that of a smaller pack due to unmanaged discounts. A distribution example illustrated how rebates and freight can turn a seemingly fine price into a problematic one if not properly accounted for. These examples underscore why focusing on unit economics is essential.)

Other Common Use Cases

While the two scenarios above cover volume-based pricing and cost-to-serve adjustments, unit pricing discipline is equally useful in other situations that SMBs encounter:

- Promotional Deals: Imagine a distributor running a limited-time promotion of 20% off a specific product category to clear inventory. A product normally priced at $100 (list) is on sale for $80. If the normal net unit price (after typical small discounts) was, say $95, this promo cut the unit price by ~16% in absolute terms. Will the volume lift make up for that margin cut? Unit price tracking, paired with volume analysis (often referred to as post-promo analysis), can reveal whether these promotions actually helped or simply trained customers to wait for a sale. Many companies find that promotions shifted sales in time or from one product to another, rather than truly creating new demand – meaning the margin give-away wasn’t worth it. With unit price metrics, you can quantify that and refine your promotional strategy.

- Bundle Pricing: Manufacturers and distributors sometimes bundle products or services (e.g., “buy our machine and get a year of spare parts included” or a kit of multiple SKUs sold together). Bundles can obscure true unit pricing if not handled carefully. The bundle might have an overall price, but internally you need to allocate that to units or have an equivalent unit measure for the bundle. Otherwise, you might have one item in the bundle that’s effectively being priced at a loss. Unit pricing discipline says: define a method to “unpack” bundles into unit economics. Perhaps you decide to allocate the bundle price across items based on weight or value. The goal is to ensure that the bundle’s unit price can be compared to the price of selling those items separately. Without this, bundles can become a loophole where margin leaks hide – a bundle might mix high-margin and low-margin items and be sold for a sum that looks fine in total, but you’ve accidentally given away all the profit on the high-margin piece. (One real example: a company bundled a profitable service with a break-even product; the bundle’s single price obscured the fact that they discounted the service so heavily in the bundle that the whole package made little profit. A unit economics view by component brought this to light so they could re-price the bundle or restructure the offer.)

The takeaway from all these examples is that unit pricing turns on the lights in the room. You see what you’re actually earning per unit sold, in every deal, and you catch misalignments that total or list prices alone would hide. Now, the natural next question is: How do we put this into practice? The concept makes sense, but implementing it in a smaller organization – without a large pricing team or expensive software – requires a well-planned approach. In the following section, we provide a step-by-step approach to start harnessing unit pricing discipline in an SMB environment.

Implementing Unit Pricing Step-by-Step

Adopting unit pricing as a strategic tool doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a process of building new habits and data views in your organization. However, it doesn’t need to be a massive IT project either – you can start with the data you have and iterate. Here’s a practical five-step sequence to implement unit pricing discipline, adapted for the realities of SMB manufacturers and distributors:

Step 1: Define Your Base Units and Conversion Rules

Before creating any fancy dashboards or reports, decide on the standard units of measure you will use for each product category. Consistency is key. For example:

- Chemicals: Decide to use $/gallon or $/kg (pick one based on how you and your customers think about volume).

- Hardware or industrial parts: maybe $/each (unit) is the obvious choice.

- Packaged foods or ingredients: $/lb or $/oz – just choose one and stick to it across that category. If one team analyzes snacks in dollars per ounce and another in dollars per pound, they’ll constantly be confused or arguing over numbers instead of insights.

Write down these base unit decisions and socialize them with all stakeholders (sales, finance, ops). Next, set up conversion factors wherever needed. If you have multiple packaging configurations, define how to convert them to the base unit: e.g., 1 case = 12 each (units); or 1 pallet = 50 cases; or 1 liter = 33.814 ounces, etc. Similarly, plan how to handle variable-weight items (where the sold quantity might vary, such as produce sold by weight) – often those are already in a base unit, like $/lb, but ensure it aligns with your scheme. The goal of this step is to create a clear map so that any SKU you sell can be expressed in the chosen base unit without ambiguity. This may involve cleaning up some data (e.g., ensuring your product master has correct units or pack sizes), but it’s foundational work that pays off. As a parallel, note that regulators (like NIST in the U.S.) emphasize standardized units for price displays – you’re doing the same, but for internal decision-making consistency.

Step 2: Capture or Calculate Net Price for Each Transaction

Many SMBs find this step to be an eye-opener, because it’s where you assemble the pricing waterfall components for the first time in one place. The objective is to mirror how finance computes net revenue, so that your unit pricing uses the true net price. At a minimum, gather the following for each order or line item:

- Invoice price (the starting price listed on the invoice or order line, often equivalent to the list price or base price).

- On-invoice discounts (any immediate discount applied, like a special price or override).

- Off-invoice adjustments that will affect final revenue, such as rebate accruals, bill-backs (credits issued later), promotional funds, etc.

- Any allowances or free goods that effectively reduce the price (e.g., buy 10 get 1 free) can be seen as a 10% discount on the invoice value in effect.

- Freight or delivery charges (or credits) if you sometimes cover freight for the customer or add freight – treat this as part of the price. If you deliver free, that’s a cost on your side that effectively lowers net revenue from that sale.

- Payment terms or financing, if applicable (for example, if you offer a 2% 30-day discount for early payment and many take it, that 2% is a price reduction in practice).

Your accounting system or ERP likely contains much of this data; it may be scattered across various modules (e.g., AR for rebates, sales for invoice price, etc.). The key is to bring it all together to calculate: Net Price = (List Price – discounts – rebates – etc.) + freight charges – freight costs. Basically, this is all the components that affect what you realize. This ensures that, for example, if you offer a customer a 5% end-of-year rebate and free shipping, your net price accurately reflects these benefits. It’s not a philosophical exercise – it’s aligning with how revenue is actually recognized (accounting standards treat those discounts and rebates as reductions of revenue). Once you have the net price per transaction, you can divide it by the quantity to obtain the net unit price. You don’t necessarily need to store this for every single line (unless useful); you can roll it up by SKU, by customer, etc., as needed for analysis. The point is that your data prep includes all the revenue adjustments.

Step 3: Normalize Units and Calculate Equivalent Unit Prices for Promos

This step is where the groundwork from Step 1 pays off. Now, take each transaction (or each SKU’s data) and express the quantity in the base units you decided. If one deal was 2 cases of 24, convert that to 48 each (if the base unit is each). If another was 5 kilograms, convert to 5,000 grams (if the base unit is grams). This gives you consistent quantity figures. Using those, compute the unit price as the net price divided by the total quantity in base units for each line or aggregated grouping.

However, if you have complex promotions or bundled sales, you need to compute the “equivalent unit price” for those. Some examples:

- Buy One Get One (BOGO) or X+Y deals: If you sold 10 units and gave 2 free, the total quantity is 12, but the revenue is for 10 units’ worth. So the equivalent unit price is (price paid for 10 units) ÷ 12 units. This will be lower than the unit price of buying one unit outright, reflecting the dilution of free goods.

- Percentage-off promotions: If 20% off, simply take the net price (which already reflects the 20% discount from the list price) and divide by the quantity – this naturally gives the lower unit price. However, be cautious if the 20% off offer has a limit (e.g., “20% off up to $100” or a more complex condition) – in such cases, calculate the effective total paid and total units.

- Bundled products: Allocate the bundle price to each component or to a common unit of measure. If it’s a fixed bundle (same items each time), one approach is to apportion the revenue by the list price share of each item to determine an implied net price per item, and then proceed to unit prices. If it’s not practical, at least define a rule: e.g., treat the whole bundle as one “unit” for unit price calculations in that category, or break it into component units if possible.

- Tiered pricing or “buy more, pay less per unit” deals: This is inherently handled by unit price calculation as long as you record the actual quantity and net revenue.

The rule here is: If you can’t compute an equivalent unit price for a certain deal structure, you can’t compare it to others. So invest time in creating rules for these scenarios. Often, it’s not very complicated – you can handle most with a few formulas. For example, for a “BOGO 50%” offer (buy one, get the second at 50% off): if one unit costs $100, then two units cost $150 under the promo. So, the equivalent unit price is $150/2 = $75 each (which is 50% off the single-unit price, not 25% – a nuance that the unit price reveals clearly). By standardizing these calculations, you make sure a promotion’s real impact is understood across the team.

Step 4: Set Guardrails and Exception Rules

With unit prices in hand (historical or live), now establish guardrails – the rules that define acceptable versus problematic pricing. For SMBs, keep these simple and focused:

- Floor prices (per unit) by category and channel: Determine the lowest unit price that remains viable for each product category, potentially varying by sales channel or customer segment. For example, you might say that product category A should never sell for less than $10/unit in direct sales, or less than $9/unit in distributor sales (perhaps distributors receive a better price). These floors could be based on cost-plus minimum margin or on strategic positioning. The point is to set a baseline guardrail.

- “Stoplight” thresholds: Some companies use a green/yellow/red system. Green = unit price is above a certain level (healthy margin), Yellow = unit price is in a risky zone (maybe within 5% of cost or below target margin), Red unit price is below an absolute floor or below cost. This helps quickly flag deals that require review.

- Customer-specific or segment-specific floors: If you have key account agreements or different price tiers for, for example, OEM customers versus small customers, incorporate those. Maybe big strategic customers have a slightly lower allowed floor (because you accept a lower margin for volume, for instance). Write these out so sales teams know their boundaries.

- Exception policies: Define when and how exceptions are allowed. Common legitimate exceptions include new product launches, end-of-life clearance, one-time strategic deals, or long-term contract commitments. For each, ideally, define who can approve and what justification is needed. For example, you might allow new products to launch at a promotional unit price below the floor for 3 months, but it must be approved by the VP of Sales and flagged as an “introductory promo” reason code. The idea is not to ban all exceptions, but to make them explicit and controlled. This way, when you later review performance, you can filter out what was a conscious strategic decision (e.g., a planned loss leader) versus what was an unintended leak.

Setting these guardrails may involve some trial and error. Initially, you might discover that a large portion of your business is below your theoretical “floor” – that just tells you the floor wasn’t realistic or your business has been underpricing broadly. Use that info to iterate: maybe you raise prices to move the needle, or adjust the floor to a more achievable level as a starting point, and then tighten it over time. The key is to set guardrails and then build reporting to monitor them: e.g., a weekly report of any sales below the floor (with totals and margin impact), or a dashboard that shows the % of volume in green/yellow/red. This provides immediate visibility to problem areas.

Step 5: Put Insights Where Decisions Happen

Finally, it’s critical to integrate these unit price insights into your team’s actual workflow. If all this analysis lives only in the finance department or in an analyst’s laptop, it won’t change anything. Some practical ways to deploy the insights:

- Dashboard or Report for Sales Team: Create a simple report (it could even be an Excel or a BI dashboard) that a salesperson or sales manager can consult before quoting a price. For instance, they could select a SKU and see “Typical unit price range for this product is $X–$Y; Floor is $Z; Last deal with this customer was $Y per unit.” This helps them frame their deal. If you have a CRM or quoting tool, see if these metrics can be integrated or at least provided as a reference.

- Regular Pricing Review Meetings: In a smaller firm, this meeting may be held biweekly, bringing together sales and finance. Review any big deals or any exceptions flagged. Look at a “margin leakage” report together – e.g., “Last month, 8% of our volume was sold below the guideline unit price, costing us an estimated $50,000 in margin.” Discuss a few specific cases (maybe the biggest contributors). The purpose is not to witch-hunt sales, but to collectively learn and adjust strategy. Over time, these meetings tend to shrink in drama because everyone is more familiar with the boundaries; they become more about forward planning (e.g., how to handle an upcoming cost increase) than post-mortems.

- Pack-Price Ladder and Margin Trend Views: Publish a simple internal report that shows for each major product line, the list unit price, the average net unit price achieved, and the unit margin. This kind of bird’s-eye view is great for product managers or GMs to spot anomalies. For example, if Product A’s net unit price is significantly different from Product B’s, even after adjusting for features/size, is that intended, or do we have an issue? Or, if the net unit price has been declining month over month for a category (perhaps due to increasing discounts or a shift in mix to larger packs), it should spark a discussion. A margin per unit trend chart can quickly show if you’re quietly losing profitability despite steady sales – often a sign of undetected price erosion.

- Tie to Incentives (if applicable): If you have incentive pay for sales or product managers based on margin or revenue, consider incorporating unit price or margin targets into your incentive structure. For instance, instead of only rewarding total sales dollars, include a metric for average selling price or gross margin. People pay attention to what they’re measured on. If they know that dropping price to hit a volume target will also hurt their performance metrics, they’ll think twice – and hopefully get more creative in finding a win-win that doesn’t rely purely on price cuts.

For all the above, start with the basics. You don’t need a perfect system from day one. Even a basic spreadsheet extract that highlights out-of-bounds deals is a good start. The key is to make unit pricing a regular part of the conversation and decision process. One mid-market company, for example, introduced a one-page “pricing scorecard” for each quarter that was distributed to all managers, showing metrics such as net unit price versus target and the number of exceptions. Just socializing that info changed behavior – nobody wants their product line to show up as the one with the most red flags. In your organization, identify the key touchpoints (such as sales meetings and leadership updates) and incorporate the unit price insights there.

By following these steps, you create a feedback loop: define standards → measure every deal against them → flag issues → act on them → refine standards. This is the essence of managing pricing in a disciplined way. It’s not about eliminating flexibility or turning pricing into a rigid formula; it’s about establishing control so that you can flex when needed – and only when needed – with full awareness of the impact.

To visualize the transformation, consider this before-and-after comparison:

| Visibility | Unit prices exist but scattered (perhaps on shelf tags or individual quotes). Net price per unit for each deal is hard to see in one place, so true profitability is often obscured. | Standard net unit price is calculated for every SKU and deal. Pricing data is consolidated into comparable $/unit terms, so you have a single view of pricing across products and customers. |

| Speed | Every pricing review or promotion analysis is a one-off project. Teams debate using different metrics (list vs net, % off vs absolute $) – it’s slow and reactive. | Regular reports provide instant answers on unit price trends and outliers. Pricing decisions speed up because everyone looks at the same unit economics (e.g. “this promo equals $0.95/unit, which is below threshold”). |

| Consistency | Different departments use different definitions (one might ignore rebates, another uses different units of measure). Pricing policies, if any, are applied unevenly. | One consistent framework – all teams use the same base units, net price definitions, and conversion rules. Exceptions are clearly documented. This alignment reduces confusion and errors. |

| Profit Impact | Margin erosion often shows up only in financial results, long after deals are done. Promotions or discounts sometimes cut deeper than anyone realized, hurting profits with little warning. | Early warning system: Unit price guardrails flag deals or promos that would drop margins below acceptable levels before they are finalized. Management can intervene in time to prevent unexpected profit hits. |

| Sales Enablement | Sales reps hear after the fact that a deal “was too cheap,” breeding frustration. They lack clear guidance on how low they can go, so they either go too low or constantly seek approval. | Sales gets clear guidelines (e.g. “don’t go below $X/unit for this product”) and examples of good deals. They have a framework to negotiate confidently. Fewer last-minute escalations, because the rules are known and followed . |

| Governance | No systematic controls; pricing approval is case-by-case and often influenced by whoever shouts loudest. It’s hard to hold anyone accountable as data is murky. | Structured governance: Defined approval paths for exceptions, routine post-deal reviews, and clear data on pricing outcomes. Accountability improves – everyone knows there’s a process and record for pricing decisions . |

(Table: How pricing management improves when shifting from ad-hoc to a disciplined unit pricing approach. Before, unit price insights were sporadic and inconsistent, leading to slow decisions and hidden margin loss. After, a standardized unit pricing framework yields transparency, faster action, and controlled pricing outcomes.)

Overcoming Common Objections

When introducing unit pricing discipline in an SMB, you might encounter some pushback or concerns from colleagues. Here are a few common objections – and practical responses to address them:

- “We already show unit prices on our labels/website, so what’s new here?” – Having a unit price on a shelf tag or in a catalog is a start, but it’s often not the full story. Those are usually based on list price and standard sizes. They don’t include the impact of discounts, rebates, or customer-specific deals. Your P&L runs on net realized prices, not list. So the internal unit pricing strategy has to dig deeper. It’s about capturing the net unit price for each transaction and using that to guide decisions. In short, the shelf tag unit price is for consumers; your unit price analysis is for managing profitability. It’s a more comprehensive and nuanced application of the concept.

- “Our data isn’t clean enough for this kind of analysis.” – It’s true that many mid-market firms have data challenges (inconsistent units of measure in the system, missing info on discounts, etc.). But you shouldn’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Start with a subset of data that matters. For example, focus on your top 100 SKUs that drive 80% of revenue – get their units standardized and gather the discount data for those. Normalize a small set of common deal types (maybe you ignore some complicated cases in the first pass). By scoping the effort, you can gain useful insights sooner and then improve data quality as you progress. In practice, going through this process even highlights where data is missing, allowing you to correct it. Over a few cycles, your data will get cleaner because you’re using it regularly. Many companies find that implementing a unit pricing discipline forces a beneficial cleanup of product information and pricing terms that are long overdue.

- “Sales will never go for rigid unit price rules or floors – they’ll fight it.” – Salespeople (or distributors, or whichever group is customer-facing) do resist pricing constraints if they feel those constraints are arbitrary or hurt their ability to close deals. The key is how you implement the guardrails. If you just say, “here’s the floor, never cross it, end of story,” you’ll get rebellion. However, if you explain the floor in terms of unit margin (“we set this so we don’t lose money; at this price we cover cost and a minimal profit”) and involve sales in setting reasonable exceptions, it goes much smoother. Sales usually fight surprises, not structure. In fact, many sales reps prefer clear boundaries because it strengthens their hand in negotiations – they can tell the customer, “I literally can’t go lower without higher approval; that’s company policy.” It takes pressure off them to discount endlessly. The other key is to show them what’s in it for them: better pricing discipline can mean more profit, which can fund better sales incentives, or it can prevent the scenario where they close a huge deal and then get blamed for poor margins. Over time, as salespeople see that management will hold the line (with rare exceptions) and that competitors aren’t always undercutting (often a fear), they come around. It helps to start with a trial or pilot in one region/product line, get a few wins, and then expand – let sales see the approach working.

- “This sounds like a big IT project – we can’t afford new software right now.” – Good news: you likely don’t need to buy anything major immediately. You can begin with the tools you have. Many companies start with an Excel or BI tool extract from their ERP: a table of invoices with quantities, revenue, etc., then add a few columns for unit price calculations. It may require some upfront work for an analyst, but it’s not a multi-million-dollar project. As you refine the process, you might invest in better analytics or a pricing module; however, the early wins come from clear definitions and simple reports, not complex systems. In fact, by doing this manually first, you will know exactly what you need from any software, which helps avoid buying an overly complex tool. There are also lighter-weight analytics solutions (including cloud-based ones) geared to mid-market budgets that can automate some of this once you’ve proven the concept. However, certainly don’t wait for a budget to start – an intern with Excel can often deliver Phase 1. The ROI on this effort can be huge, so it may even justify future tech spend if needed (with far better clarity on requirements).

By addressing these objections with a clear-eyed view, you can gain buy-in. Remind everyone: the goal isn’t to make life harder, it’s to make the business stronger. In many cases, once the team sees the insights from a pilot analysis (like “did you know 15% of last quarter’s orders sold below our cost?” or “look how inconsistent our pricing is for the same item”), the resistance fades and people want the solution.

Putting It All Together and Next Steps

Implementing unit pricing as a strategic discipline can feel like a significant change, but it’s essentially about presenting the right data to the right people at the right time. To recap a practical way forward:

- Perform a Diagnostic on a Sample of Data: Select a representative slice of your recent sales (such as one product category or a major customer) and follow the steps – calculate net unit prices, examine the variation, and determine where prices align with costs or targets. This “diagnostic” exercise often uncovers quick wins or glaring issues (e.g., a specific customer consistently receiving the lowest unit price). It also helps refine your approach before scaling up.

- Quantify the Opportunity: Use that diagnostic to estimate the upside. For example, if you found that bringing the bottom 10% of prices up to a floor would add $X to profit, that’s powerful. Many executives will support the initiative when they see the dollar impact of tightening up pricing. A famous McKinsey study noted that a 1% improvement in price can yield an 11% improvement in operating profit. Ask your team: What would 1% more on our net unit prices mean for us? Often it’s significant.

- Secure Cross-Functional Buy-In: Present the findings to both finance and sales (and anyone else relevant). Frame it as fixing leaks and ensuring fairness (we want consistent, rational pricing). Emphasize that this is not a punitive project, but one that can fund growth, protect jobs by improving margins, and so on. If you can, get a senior sponsor (like the CEO or GM of the business) to emphasize the importance of pricing discipline.

- Develop the Playbook: Create a concise pricing playbook or policy that outlines the base units, the methodology for calculating net price, and the guardrails/exceptions. Keep it to a few pages – enough to be clear, not so much to be ignored. This serves as a reference for everyone and for onboarding new team members into the approach.

- Leverage Tools (but Start Simple): As mentioned, begin with existing tools. Your ERP, combined with Excel or a business intelligence tool, can accomplish a great deal. Over time, you might integrate these calculations into a more automated dashboard. The goal is to reduce manual effort on data prep so the team can focus on analysis and action. However, be wary of jumping to buy software too early – first nail down exactly what you need to measure and manage. Then, if needed, explore tools that are designed for mid-market (there are pricing analytics platforms “as a service” that align well with companies that don’t have internal IT for this – more on that in a moment).

- Monitor and Adjust: Once you roll out unit price metrics and guardrails, monitor the impact. Are fewer deals falling below the floor? Did average unit prices actually increase in your target areas? Is sales feedback improving? Use these to iterate. Perhaps you can tighten the floor next quarter if it was easily achieved, or maybe you found that some products can actually command higher prices once you saw the data and adjusted your list prices upward. Unit pricing strategy is not a one-time project; it’s an ongoing management practice. However, it becomes easier and more ingrained with each subsequent cycle.

Finally, consider if you might benefit from some expert help or tools tailored to this need. This is especially relevant if you feel that you don’t have the internal bandwidth or expertise to sustain the effort. There are solutions in the market aimed at exactly mid-sized manufacturers and distributors who want to improve pricing without massive investment.

One such partner is Revify Analytics (myrevify.com) – a firm that specializes in helping mid-market companies identify and address price leakage, thereby boosting margins through enhanced analytics. Revify offers a proven approach that lines up well with what we’ve discussed. Their platform is purpose-built for companies in the ~$10M to $2B range, meaning it’s **designed to handle large SKU counts and transaction data without the heavy cost and complexity of enterprise software】. It can consolidate your sales, cost, and pricing data into intuitive, real-time views, allowing you to spot hidden revenue and profit leaks at a glance. For example, Revify’s dashboards highlight which SKUs or customers are below target price or margin, and by how much, connecting the dots between your costs, volumes, and price realization. This instant visibility helps you prioritize – you’ll quickly see which products or accounts are dragging down your average unit prices or where discounting is most out of control.

Moreover, Revify’s approach isn’t just software; it includes expert guidance. Every subscription comes with support from seasoned pricing and revenue management experts. They act as an extension of your team, helping to interpret the data and recommend actions – effectively the “surgeon” to the X-ray, to use an earlier analogy. This can be hugely valuable for an SMB that doesn’t have a full-time pricing analyst. They can assist in setting the right guardrails, identifying the biggest opportunities (for example, “your top 10 margin leaks are here, fix those first”), and even help coach your team through making the necessary price changes. The model is often described as “Revenue Growth Management as a Service,” where you receive both the analytics platform and ongoing expert input in a subscription format. The benefits are speed and flexibility – they typically can get you up and running in a matter of weeks, not months, and do so in a cost-effective way (no big upfront license, minimal IT burden).

In practice, partnering with a firm like Revify Analytics means you can accelerate the implementation of everything we’ve discussed. Rather than reinventing the wheel, you tap into a ready-made toolkit of metrics (such as net unit price by SKU/customer, price vs. floor, and margin waterfall) and a team that has seen these patterns before. They can help you run that initial diagnostic, set up the monitoring dashboards, and embed the process into your routine. And as your business evolves – say you add new product lines or face new market pressures – they update the analytics and advice accordingly. The goal is to ensure that the pricing improvements aren’t one-off, but continuous – a persistent framework that keeps finding the next dollar of profit for you.

Whether you use an external partner or go DIY, the key message is: SMBs can indeed manage complex pricing in a sophisticated way – without needing Fortune 500 resources. Unit pricing is the doorway into that sophistication. It’s a simple concept on the surface, but when systematically applied, it unlocks insights that are often startling. By knowing your true price per unit and actively managing it, you can stop the margin leaks that have been quietly draining your business. Those recovered margins can be reinvested in growth, used to buffer against cost increases, or dropped straight to your bottom line.

In today’s competitive and inflationary environment, pricing is one of the most powerful levers you have. You may not be able to control your input costs or the overall market demand, but you can control how you price and where you draw the line on unprofitable business. Unit pricing gives you that control in a granular, actionable form. It helps transform pricing from a chaotic scramble (“who approved this discount?!”) into a strategic function (“we improved net price by 2% this quarter by optimizing our mix and tightening discounts, which added $X to profit”). For an SMB, that can be the difference between struggling and thriving.

Next Steps: If you haven’t already, start by evaluating your own pricing data. Pick a product or customer and calculate the unit prices – see what story the numbers tell. This hands-on step can energize your team to dig deeper. And if you want to fast-track the journey, consider reaching out to experts like Revify Analytics, who have helped many businesses like yours find millions in hidden margins and build pricing discipline that lasts. With the right tools and approach, even a small team can punch above its weight in pricing strategy.

In summary, unit pricing is far more than a math exercise – it’s a strategic lever. For small and mid-sized manufacturers and distributors facing pricing complexity, treating unit price as a key performance metric and management focus can unlock significant profitability. It enables you to manage thousands of SKUs and dynamic market conditions with clarity and confidence. By implementing the steps and principles outlined in this guide, you’ll be well on your way to tighter pricing, higher margins, and a stronger competitive position in your market. And remember, you don’t have to go it alone – proven partners and platforms are available to help you turn data into profit, quickly and affordably. Here’s to taking control of your pricing and boosting your profitable growth!